[Editor’s note: This interview was conducted in 2017.]

The work of Dr. Richard Perez has been integral to the success of the solar industry. He developed the mathematical model used to predict how much irradiance (solar energy) will be on solar panels at different times throughout the year based on weather patterns. Perez’s model has been incorporated into many software modeling programs, including Aurora’s. It enables solar designers to more easily and accurately predict how much light will be available to different solar installations, and therefore how much energy they will be able to produce and what financial returns they will offer.

Dr. Perez is a Senior Research Associate at the Atmospheric Sciences Research Center, State University of New York at Albany, where he directs applied research and teaches in the fields of solar radiation, solar energy applications, and daylighting.

Dr. Perez is a Senior Research Associate at the Atmospheric Sciences Research Center, State University of New York at Albany, where he directs applied research and teaches in the fields of solar radiation, solar energy applications, and daylighting.

We had the privilege of talking with Dr. Perez to learn more about his research and its applications in the solar industry, as well as his thoughts on future industry trends and the changing role of weather modeling research.

Tell us about yourself, and your involvement in the solar industry.

I’ve been in the solar industry for over thirty years now. I started in the early 80s, and I am a research professor at the University of New York at Albany. I develop solar resource (solar radiation) models.

Since day one, I have been also interested in solar energy applications. In fact, my students and I installed one of the very first systems in New York City on the rooftop of the Lincoln Center—before it was a business to do that. We also powered a radio station at a local university. These were the early projects. Back then, doing solar resource research and the actual installations were one and the same.

Installation slowly became a business, so I moved away from that, and I continued the solar resource research. But I always keep an eye on the nuts and bolts of solar design.

All of the research work I do is geared toward putting more solar on the grid one way or another. That’s my driving motivation.

We could reach 100% [renewable energy] easily in my opinion. As the proportion of renewables increases, you will really want to manage that flow of power, accounting for weather changes the best way you can… that’s where [weather] models are going to become really important to drive those systems.

How would you explain your irradiance models to someone who is not familiar with them?

The first model I developed, which I was lucky to gain recognition and subsequent funding from, was designed to calculate the irradiance on a tilted plane in an arbitrary orientation, from basic Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) data.

[Typical Meteorological Year data is the most common way to describe the average local climate from the perspective of solar applications. It is developed based on hourly meteorological measurements over many years to build a picture of the typical weather conditions.]

I was lucky to develop that model at the right time and the right place. There was an International Energy Agency study comparing all the different models on the planet to do that kind of thing and my modeI was ranked first. Since then, that model has been embedded in all kinds of software.

Later, in the early 90s, I became interested in using satellite remote sensing to get solar data, because satellites are up there 24/7 and see the whole planet. You can actually get data anywhere you want on the planet if you have a good model to do that. So I started satellite model development and I worked with a company in California, called Clean Power Research. Our model materialized into something called Solar Anywhere, that many people use today to get data.

This model has since been built upon to support forecasting, which is a big focus these days. We are developing a lot of forecasts, trying to predict, for instance, how much energy will be produced from solar tomorrow at 3 p.m. in a certain location—to help the integration of PV on the grid by making it easier for utilities to better manage that power.

I think the long-term trend is that to better manage [solar energy] on the power grid, it’s going to be curtailed somehow… it’s going to cost less to overbuild PV than to, say, put in things like storage.

How is your model applied to energy production simulation?

It gives you a more accurate reading of how much a solar system is going to produce given its orientation and tilt; shading can then be factored in on top of that. It lends itself well to complex simulations in any orientation.

Some of the [earlier] models worked pretty well for panels facing due south, but they became less accurate when applied to panels facing east or west or north. The model I developed is robust enough to work in any circumstances.

I predict that eventually models and related software will evolve to the point where you will simulate data in real time from all the systems you have installed, using satellite data and forecast models linked to that data.

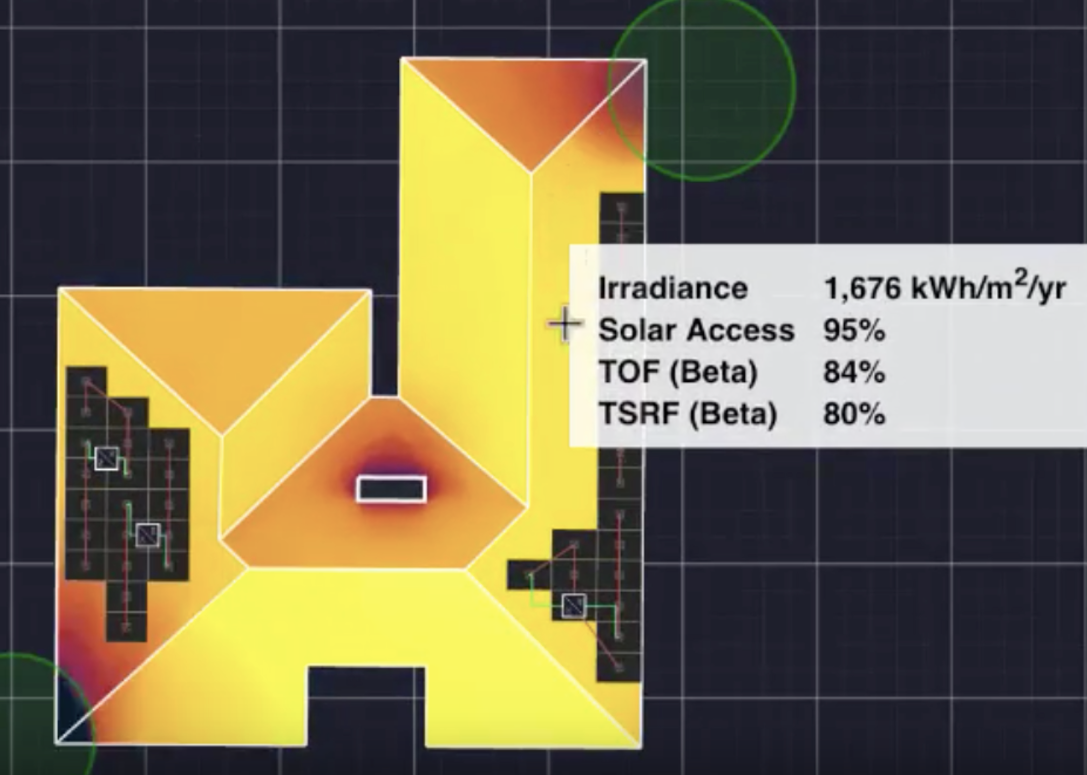

[Note: Dr. Perez’s model is built into Aurora’s irradiance engine. This mathematical analysis is applied to TMY data from local weather stations to develop an irradiance map of the site, such as the one shown in Figure 1 below, which provides solar energy values (kWh/m2/year) at each point across the rooftop.]

Figure 1: An example of an irradiance map produced with Aurora’s irradiance engine.

Figure 1: An example of an irradiance map produced with Aurora’s irradiance engine.

How does accurate weather modeling affect the solar industry at large?

You want to be able to predict exactly how much energy your system is going to produce so you can make a good economic assessment of your system. That was especially true a long time ago when PV cost a fortune so you really wanted to optimize designs.

Today, PV is getting cheaper and cheaper. I think the long-term trend is that to better manage it on the power grid, it’s going to be curtailed somehow, because it’s going to cost less to overbuild PV than to, say, put in things like storage. So there will be an optimum management. In that case, the model will not be as critical to making the economics work.

However, it’s going to be really important to manage the flow of solar power on grids. Renewable energy penetration is increasing…. We could reach 100% easily in my opinion. As the proportion of renewables increases, you will really want to manage that flow of power, accounting for weather changes the best way you can, and that’s where all of the models are going to become really important to drive those systems.

Your model has been the industry standard for decades. How do you predict that irradiance modeling will evolve over the next ten years?

Over the next ten years, I think it will evolve to focus on energy flow management, so forecast models will be the models most in need to do solar energy calculations.

I predict that eventually models and related software will evolve to the point where you will simulate data in real time from all the systems you have installed, using satellite data and forecast models linked to that data. That information could be transmitted to the people that operate the power grid so that they can make sure all those systems are working perfectly. That will enable us to put tons of renewable sources on the grid without breaking the system.

Does climate change affect the Typical Meteorological Year in a way that would impact solar energy production?

Well, there is a lot of research going on on that. Based on everything I’ve seen so far for solar, it’s a very mild effect. A couple percent here and there. On a yearly basis, it’s not going to change all that much from all the simulations I’ve seen.

Unless you live in the Northern-most latitudes, like above 60 degrees latitude — then you will probably have more clouds up there. With Arctic melting, there will be more water leading to more clouds.

But in the US, and similar latitudes, solar resource availability is going to be pretty much the same. I’ve seen simulations that go 100 years in the future taking into account climate models and I’ve not seen anything that shows me that solar will decrease significantly.

What current research in weather or solar energy production modeling do you find particularly exciting?

Because solar energy production is variable based on the weather and time of day, it’s not a consistent power delivery mechanism for now. However, there are ways to optimize that with the right amounts of batteries, oversizing, demand-side response load control, and geographic dispersion.

You can optimize all of that, and you could deliver close to 100% penetration PV at a very reasonable price. Achieving that optimum and driving it is really what excites me right now.

~~~~

Enjoyed this post? Subscribe to our blog to be updated about new articles.

Background photo credit: Warren Gretz / NREL